COVID-19 Online Screening Tool: Answer on your smartphones or computers within 24 hours prior to your visit to The Medical City.

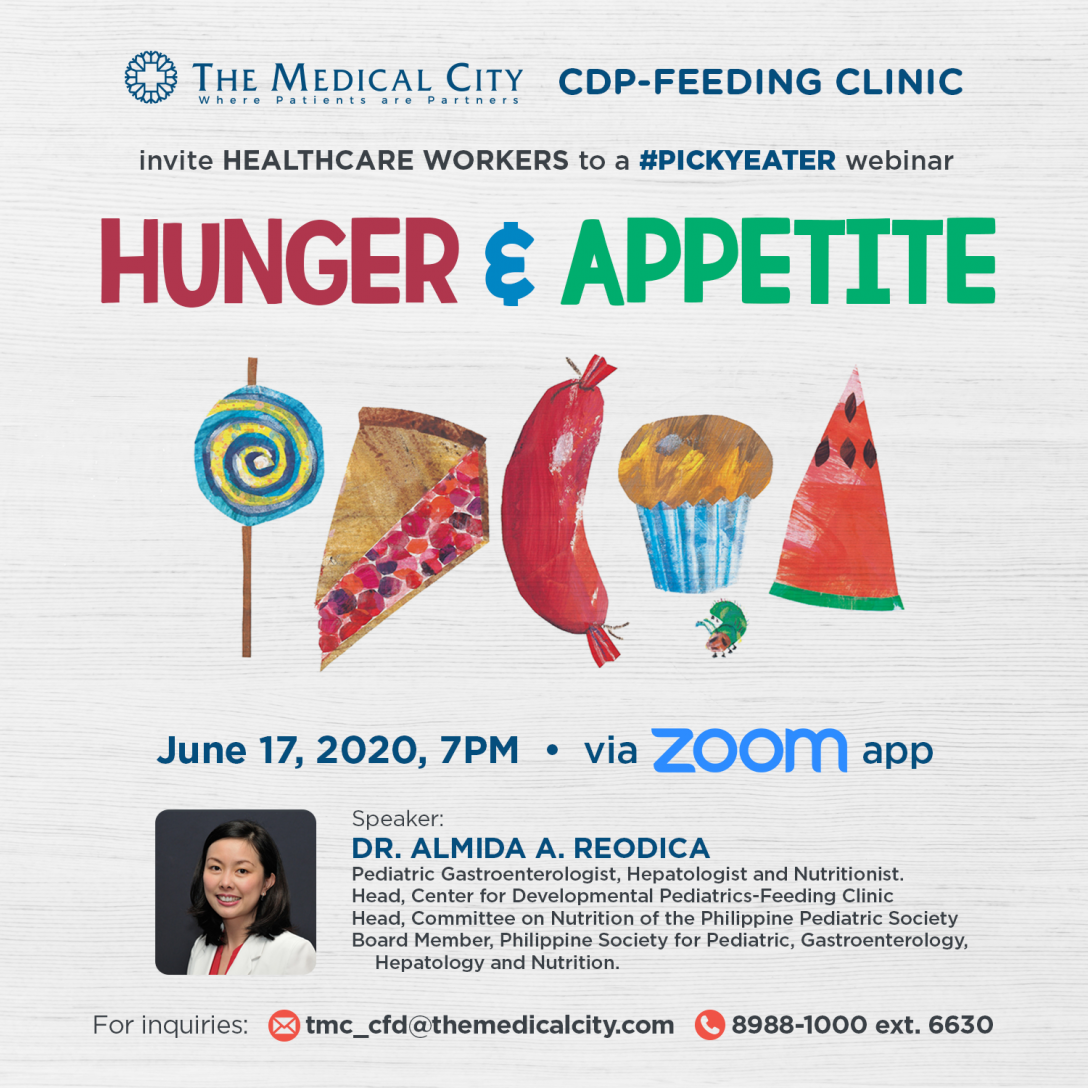

Managing Your Child’s Nutrition: Knowing the Difference Between Hunger and Appetite

By The Medical City (TMC), Ortigas | July 01, 2020

Parents often confuse hunger and appetite but when it comes to your child’s nutrition, knowing the difference between the two can make a big impact.

Parents often confuse hunger and appetite but when it comes to your child’s nutrition, knowing the difference between the two can make a big impact.

The Feeding Clinic under The Medical City (TMC) Center for Developmental Pediatrics (CDP) recently held a Picky Eater webinar titled “Hunger and Appetite” with pediatric gastroenterologist Dr. Almida “Mitzi” Reodica as the resource speaker.

Early childhood nutrition, especially during the first 1,000 days of life, is essential in a child’s growth and development. As such, it is important for parents and those managing pediatric health and nutrition to understand the difference between hunger and appetite to help determine the best course of action.

The Role of Hunger, Appetite, and Satiety in Childhood Nutrition

Hunger is defined as a set of feelings or internal experiences necessary for a person to seek food while appetite is the preference that surrounds the selection of food available with or without the presence of hunger. The culmination of processes associated with the end of the meal is referred to as satiation.

Dr. Reodica also described hunger as an essential trigger that makes people want to eat. She detailed the different phases of hunger to better illustrate what happened when a person does become hungry.

- Phase I – Prolonged period of quiescence or inactivity (40-60% of the time)

- Phase II – Increased frequency of action potentials and smooth muscle contractility (20-30% of the time)

- Phase III – A few minutes of peak electrical and mechanical activity (5-10 minutes)

- Phase IV – Declining activity which merges with the next phase I

How these are regulated is affected by factors such as hormones, the nervous system, and intestinal muscles. By understanding the different phases of hunger and how it is regulated, we are able to determine possible controls when to help in the nutritional management of children, and even adults.

Hunger and satiety may be affected negatively by gastrointestinal illnesses, medications, stress, and heavy meals prior to schedule mealtimes. As such, it is important to determine if any of these factors are present whenever a child says he or she is not hungry.

Appetite, on the other hand, is affected by a whole variety of factors such as homeostatic mechanisms (eating for calories and pleasure), hedonic mechanisms (eating just for pleasure), genetic predisposition, first taste, and family experiences. These different factors in appetite, along with the environmental influences, affect a child’s behavior towards certain food and eating.

By understanding factors affecting hunger, satiety, and appetite, primary caregivers can address the root cause and work around it to help the child eat and acquire the necessary nutrients he or she needs.

The Role of Family in Children’s Appetite

More than the biologic predisposition of children when it comes to appetite, the environment and experiences they have when they eat play a vital role. It is for this reason that the family plays a vital role in ensuring that children get the best nutrition by making mealtimes enjoyable and pleasurable.

Here are five tips to help parents make sure their children enjoy getting the nutrition they need:

- Don’t force food on the children. Avoid force-feeding children. Offer the food but allow them to try it at their own pace.

- Make it a sensory experience. Allow the child to have a full sensory experience by looking at the food, smelling it, and feeling its texture before trying to taste it by licking and eventually biting, chewing, and swallowing it.

- Revise your grocery list. By ensuring that only healthy food is available at home, children will have no reason to look for non-nutritious food because it is unavailable. If at the beginning they are not exposed to junk food, they will not look or crave for them even when exposed later in life.

- Make mealtimes time for the family. Take it as an opportunity to bond and make it a positive experience for the whole family

- Build a support system. Make healthy eating something for the entire family. Set an example, be encouraging, and provide the support they need.

If you find your child picky, fearful, or fussy when it comes to eating, then you may benefit from part him or her.

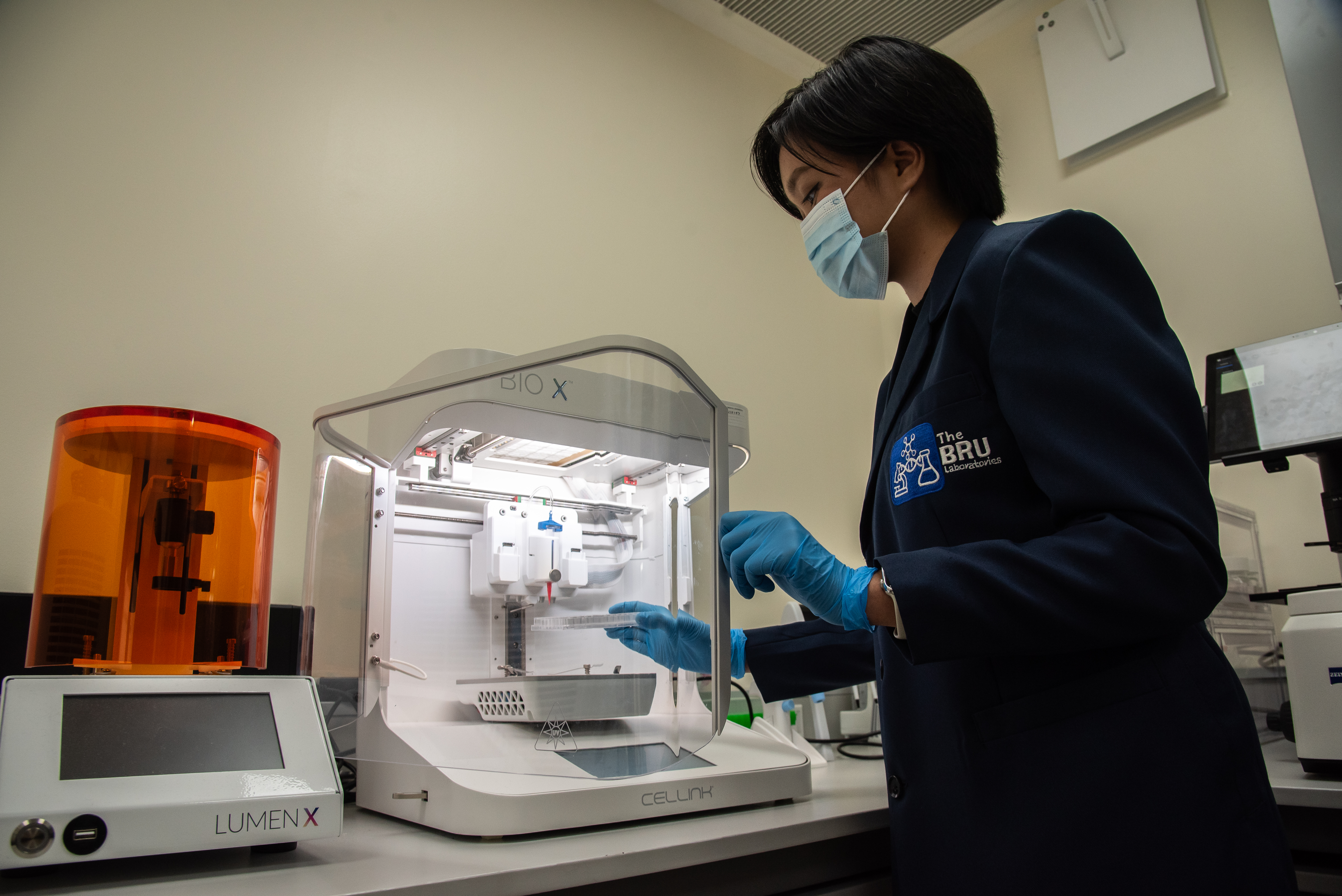

The Medical City’s Center for Developmental Pediatrics Feeding Clinic is the first of its kind in the country. Staffed by a team of healthcare professionals, it provides a holistic multidisciplinary approach to managing feeding difficulties from the common to the most severe cases.

For inquiries, you may contact the Center for Developmental Pediatrics at 8-988-1000/8-988-7000 Ext. 6630 or email them at tmc_cfd@themedicalcity.com.

Related News SEE ALL NEWS

Health

The Gift of a Second Life

Health #MyTMCExperience Press Room

She Thought It Was Just Heartburn—It Was Actually a Heart Attack

Health Research

Tissue Engineering for a Future without Organ Shortages

Health Press Room

Chikiting Ligtas: Addressing the Gap in Immunization Coverage

Health Corporate

Notice to the Shareholders of Professional Services Inc. (PSI)

Health Corporate

Notice to the Shareholders of Professional Services Inc. (PSI)

Health Corporate

Notice to the Shareholders of Professional Services, Inc. (PSI)

Health #MyTMCExperience

Friendship goals: See the world better, TOGETHER

Health #MyTMCExperience

#MyTMCexperience: Rod Cruz

Health TeleHealth COVID-19

Back to Health, Back to the City

Health Corporate Advisories

Notice of Annual Meeting of Stockholders

Health Corporate

Pedalling through Safety

Health

Diabetes and COVID-19

Health

FAQs on Patient Portal

Health

2021 Holy Week Schedule

Health

How serious is fatty liver?

Health Desk of the President

Oxford Business Group: The Report 2021 - Addressing the Gaps

Health TeleHealth

Need an advice from an Orthopedic Specialist?

Health

Welcome 2021 in good health

Health

Change Your 2020 Vision

Health COVID-19

Convalescent Plasma Donation for COVID–19 Survivors

Health

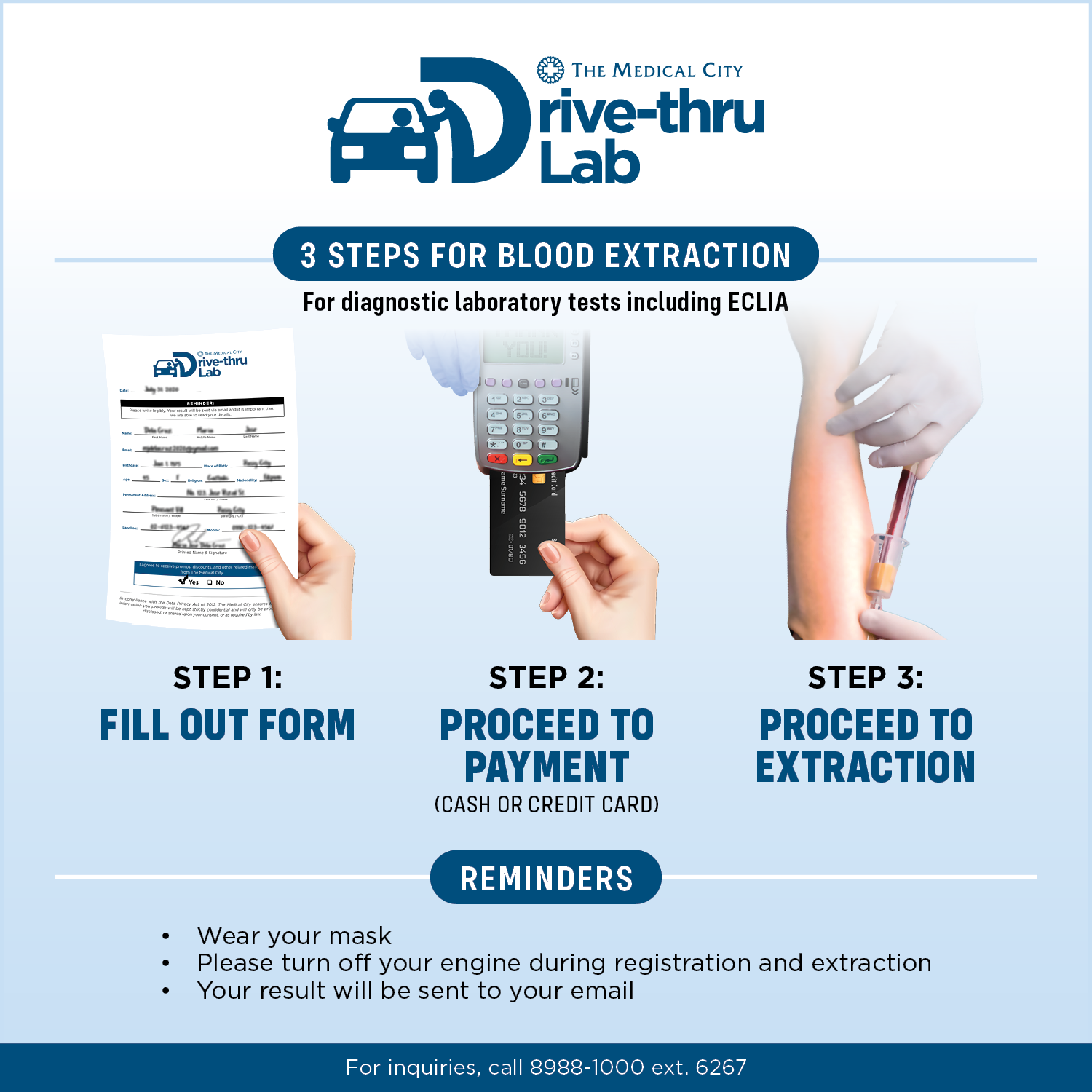

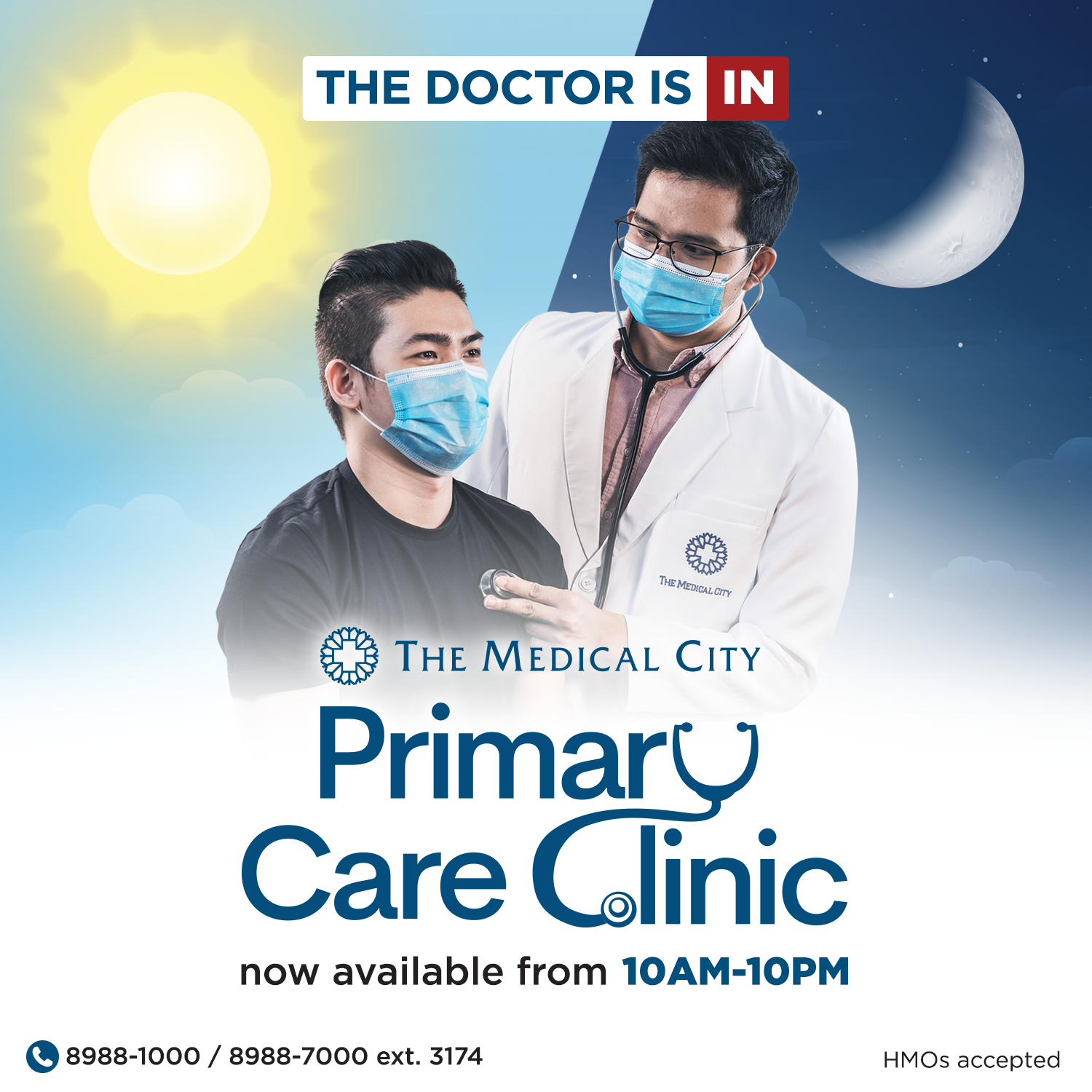

FAQs on TMC Drive-thru Lab

Health

Be in and out in 90 minutes

Health

Schooling in the New Normal

Health

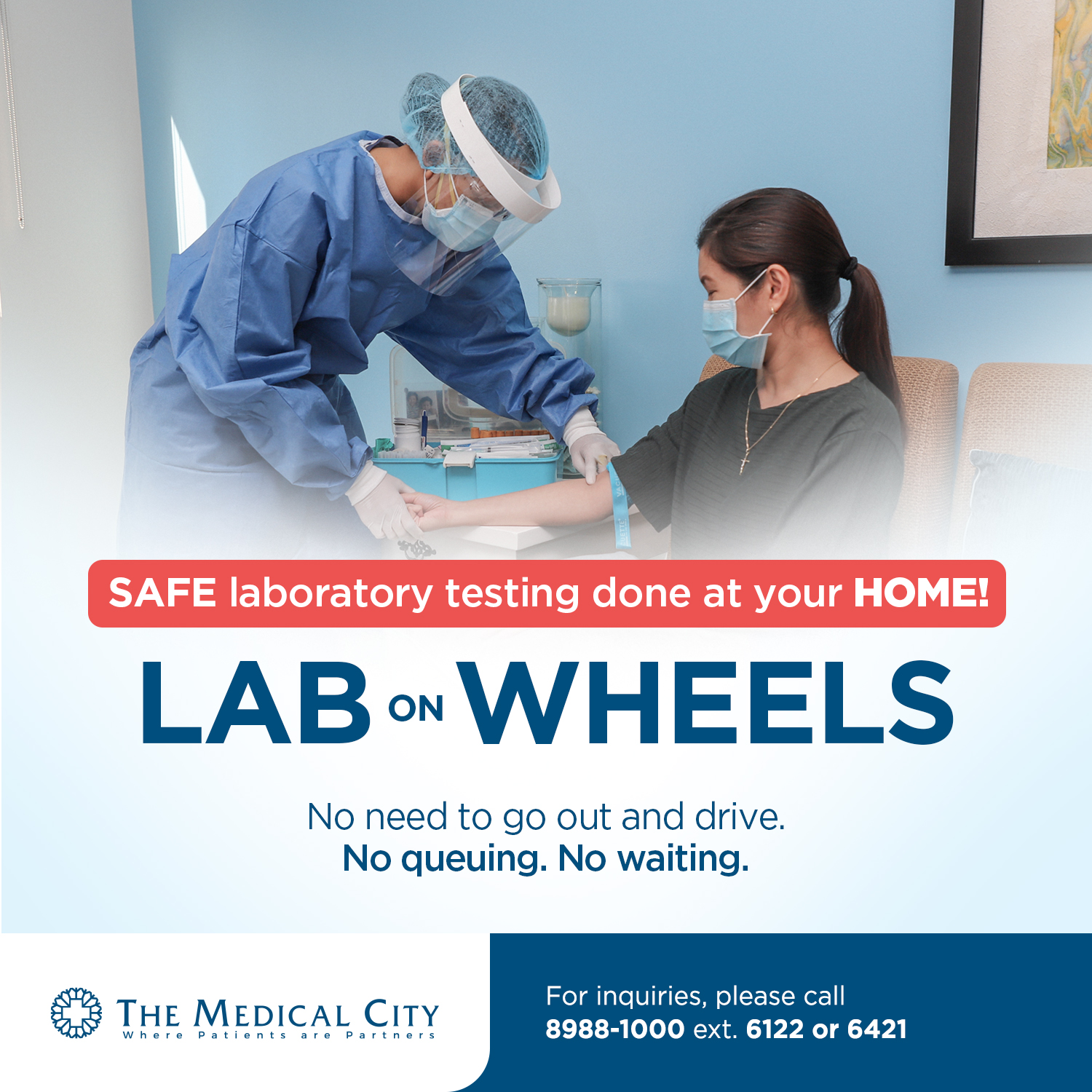

TMC Lab on Wheels

Health

Autism

Health

Eye Health in Computer Work

Health

Speech Delay

Copyright © 2020 The Medical City. All rights reserved.